A tale of colonialism and survival

Who would have thought that the creation of wine was utilitarian by nature? The establishment of wine farms is so often framed through its well-deserved stunning lens. The rolling hills, Cape Dutch architecture. However, it was not born from indulgence or traditions that we see today.

Taking a time machine to 1650 South Africa, life would instantly look different. Agricultural outposts are part of a colonial supply chain, routes are linked to the empire, and wine is viewed as a medicine. An image of survival begins to take shape.

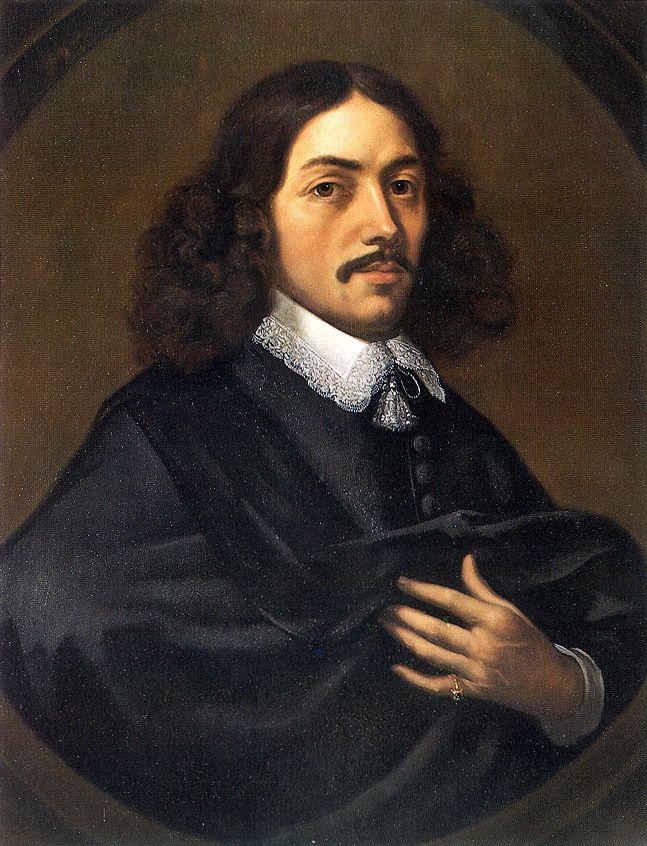

The year is now 1652, Jan van Riebeeck has settled in South Africa. Through Jan van Riebeeck’s marking of the start of the Cape Colony, the Dutch East India Company had just established itself.

The Cape has transformed into a port for ships travelling between Europe and Asia. The journey was treacherous; fresh food was scarce. Wine was believed to contain medicinal properties for ailments such as scurvy.

Fast forward seven years, it’s 1659, and Jan van Riebeeck’s is the first recorded wine to be produced. However, it was not for enjoyment but out of pure necessity.

The wine was not intended for commercial use – it was not refined. But it was an experiment that quickly became the start of viticulture in the Southernmost tip of Africa.

What followed was an entire transformation of the area. Scattered vineyards turned into formal farms, and suddenly, wine farms began dominating the lands.

It’s now 1685, and the first official wine farm has been established. The then Governor of the Cape, Simon van der Stel, was gifted a vast majority of land near the slopes of Table Mountain. He named the land Constantia, and his was the birth of one of Cape Town’s most influential wine estates. This land would later be divided into Groot and Klein Constantia.

Constantia wines gained international notoriety as early as the 18th century, as they were exported to Europe and praised in royal courts. It’s reported that figures such as Napoleon enjoyed the wine during his exile. It’s said that at his deathbed, one of his final requests was a glass of the sweet wine. The sweet wine to this day is known as “Napoleon’s wine.”

Cape wine became a global luxury; Marie Antoinette, Queen Victoria, and plenty of other famous figures would consume cases of the Cape wine.

The success of Constantia wines led to the boom of wine estates across the winelands.

During the 1680s and 1690s, wine estates expanded rapidly, birthing some of the most well-known wines to date.

Muratie

Founded in 1685, Muratie’s origins are unusual. The land was originally granted to a German official of the Dutch East India Company, who later married a formerly enslaved woman who became the earliest documented female landholder in the Cape.

Unlike other estates, typically built on grand agricultural statements – this farm developed slowly and was shaped by family inheritance. Over the centuries, the estate was passed through multiple hands, facing constant ownership change and frequently operating on a smaller scale. Muratie has never become a dominant exporter or a fashionable name – which helped preserve the brand.

Muratie is a testament to endurance and quiet continuity. A working farm that resisted reinvention and its wines, still to this day, are traditionally structured, distinctive and echo the history.

Meerlust

The land that Meerlust sits atop was granted in 1693, and the estate stands out for its remarkable continuity of purpose. The farm has been owned by the Myburgh family since the 18th century, developing a reputation for reliability. Its Cape Dutch homestead, which was completed in 1776 remains one of the most recognisable markers of early wine wealth.

Meerlust has remained steadfast throughout generations. It’s flagship wine, Rubicon, would become symbolic of South Africa’s post-apartheid re-entry into the global wine market – after rigid controls and sanctions during that period.

Boschendal

The original title deeds date to 1685, placing this popular wine farm among the earliest formal farms in the Cape. Strategically located between Stellenbosch and Franschhoek, it occupied a corridor that supported grain, livestock, fruit and of course – wine.

Unlike other wine estates that often appear linear, Boschendal’s past is marked by interruptions left and right. Ownership shifted – the identity of the farm became fractured, prioritising bulk agriculture and not viticulture. It wasn’t until the late 20th century and early 21st century that the farm reestablished itself as a model of Cape Heritage and wine production.

Architecture was restored, the land rehabilitated, and food and wine became integrated into the broader estate experience. Today Boschendal is known for standing the test of time.

Vergelegen

Possibly one of South Africa’s more celebrated wine farms that emerged in 1700. At the turn of the 18th century, Vergelegen was established by Willem Adriaan van der Stel.

The estate represented wealth, ambition, and agricultural confidence. However, its vineyards were later destroyed amid political scandal. The estate was eventually replanted and today operates under the original name. An example of historical revival rather than continuous production through the ages.

These wine estates reveal a history that mirrors South Africa’s own: complex, fractured, and deeply interwoven with the land. Their survival is not accidental, nor is it entirely romantic. It is the result of adaptation, endurance, and the ability to hold history without being trapped by it. What remains today is a culture shaped by everything it has lived through, and stronger for it.

They reveal how inheritance laws, colonial politics, economic collapse and agricultural necessity have shaped South African wine culture.

These farms were never designed to become heritage destinations; they survived because they served a purpose – to families, to local communities, and to a global market. In doing so, they cemented South Africa’s reputation as a resilient wine-producing nation and a long-standing exporter of globally recognised wines.

Today, South Africa exports approximately 306 million litres of wine annually, supported by around 2,350 grape producers and more than 500 wineries that form the backbone of the national industry.

While historic estates continue to anchor the country’s wine identity, a growing number of independent producers are shaping its present and future. From boutique, small-batch winemaking to large-scale operations such as KWV and Nederburg, South Africa’s wine landscape allows for both scale and intimacy.

For newer wine farms, entering this space means navigating a trade defined by centuries of history while still carving out a distinct identity. It requires balancing respect for inherited knowledge with the realities of modern production, climate pressures, economic sustainability, and evolving global tastes.

It is within this context that estates such as Bizoe have emerged: not as a rejection of tradition, but as a continuation of it, shaped by personal vision rather than legacy alone.

Speaking to this balance, Rikus Neethling, founder and winemaker of Bizoe, reflects what it means to build a contemporary wine brand within one of the world’s oldest winemaking cultures. He mentioned that “The wine world is built on tradition, but it stays alive through reinterpretation. As a newer brand, we respect the past deeply, and that respect gives us the permission to continuously evolve.”

Rikus’ perspective underscores how South African wine continues to evolve, not by erasing its past, but by allowing new voices to engage with it.

Image credit: Supplied

Never afraid of an em-dash or trying new places across the world. Shelby thrives on sharing her favourite restaurants, cafes and hole in the walls. If she’s not eating out she’s at home trialing new recipes in her kitchen while binging series.